Newfoundland Trade

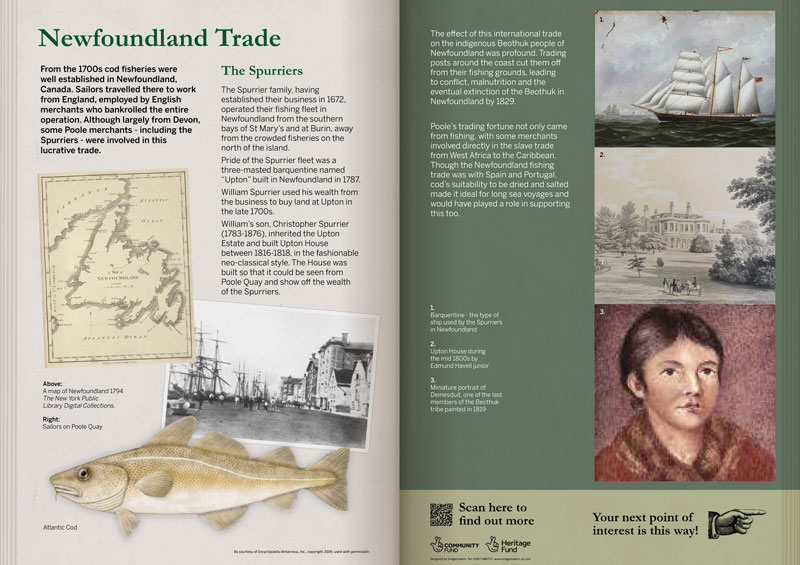

From the 1700s cod fisheries were well established in Newfoundland, Canada. Sailors travelled there to work from England, employed by English merchants who bankrolled the entire operation. Although largely from Devon, some Poole merchants – including the Spurriers – were involved in this lucrative trade.

The panel in the Park

The Beginnings

In 1497 Giovanni Caboto, a Venetian navigator, set sail from Bristol and found what he called the New Land. His discovery started the “Newfoundland cod trade”. He came back with reports of the abundant waters:

‘The sea there is swarming with fish…..I have heard this, Messer Zoane (Caboto) say that they could bring so many fish that this kingdom would have no further need of Iceland….’

Report to the Duke of Milan, December 1497

In 1502, the ‘Gabriel of Bristol’ brought to England the first recorded cargo of cod (36 tons), however it was largely the French and Portuguese who exploited the fisheries in the early days.

The Involvement of Poole Merchants

Newfoundland lies on the East coast of Canada. Its lucrative fishing grounds led many families to emigrate from Poole to Newfoundland in the 1700s and 1800s. That is the reason that today over 20% of Newfoundlanders can claim their ancestors came from Poole.

A map of Newfoundland 1794. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Englishmen tended to fish in the eastern shore of the Avalon Peninsula. People from different parts of the West Country tended to occupy their own particular towns. Exeter men, for example, tended to fish in St Johns and bays in that vicinity. Men from Poole occupied and developed the area round Trinity and many street names in that area still bear witness to this. The Spurriers set up their business in St Mary’s Bay, on the other side of the peninsula from the other Poole merchants, where there was less competition and where they could get their catches earlier than those further north.

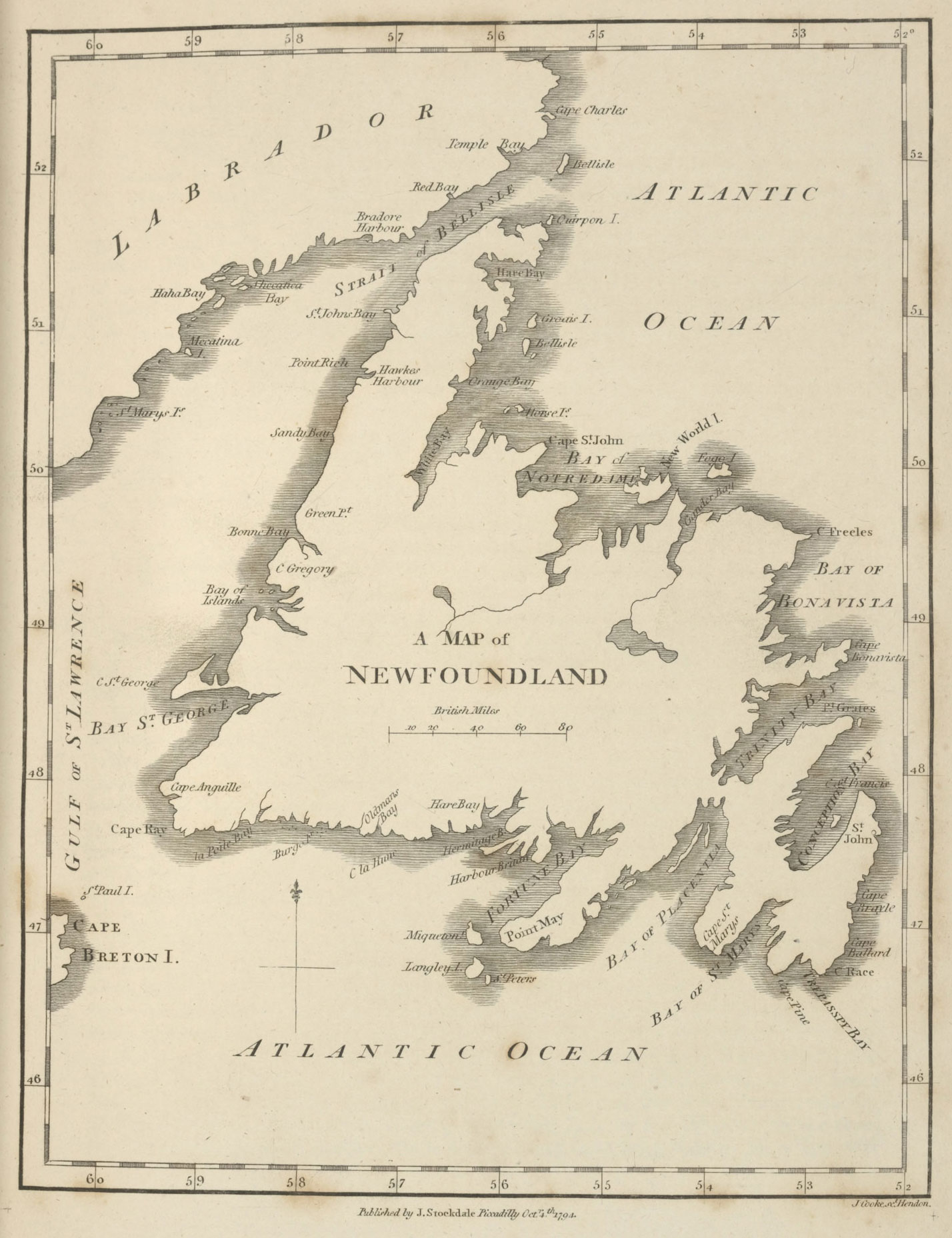

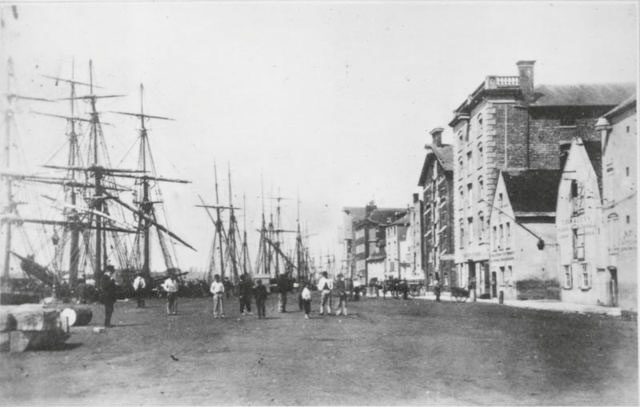

Cod fuelled Poole’s golden age. The port was busy with ships taking men and supplies over to Newfoundland, then returning via Southern Europe with cargoes of wine, olive oil and fruit.

Courtesy of Salcombe Maritime Museum

The Georgian legacy of mansions and public buildings in Poole were built on the vast profits made by the merchants who dominated the trade. Mansion House in Thames Street (Benjamin Lester’s residence) is a good example. A few of the men who became ‘cod’ wealthy were Samuel White, Benjamin Lester and John Slade. Their families dominated Poole’s political and economic life for almost 200 years.

Why cod was so important

Cod is a large fish that can breed fast. A cod a metre long can produce three million eggs in a spawning and can live for 20 years. When food is plentiful and predatory man is in relative absence – as was the case, at the Newfoundland Grand Banks in the 1500s, there were reports that the sea was churning with fish and some were nearly as big as a man. As a greedy fish, cod is also quite easy to catch.

Cod flesh has little fat in it so when it is salted or dried, it rarely spoils. It was therefore highly significant in the Middle Ages as a long lasting source of protein. It could be kept for over ten years and transported long distances to be used in many different ways. This was a central issue for the development of the trade.

Demise of the Trade

Over-exploitation of cod during the 1800s was only part of the reason that forced the inshore fishery into decline. A more profound factor was Anglo-French warfare (Napoleonic Wars) which disrupted the fisheries, and the markets as many vessels would have been sunk along the European leg of the trade route. By the 1830s the Newfoundland trade had all but died out as control of the fishery passed from West Country merchants into the hands of the Newfoundlanders themselves.

There was a revival of the Newfoundland Trade in the 1860s but many Poole merchants no longer had an interest in this. Certainly for Christopher Spurrier, the initial decline of the trade was enough to help send him into bankruptcy.

The Impact on the Indigenous Population of Newfoundland

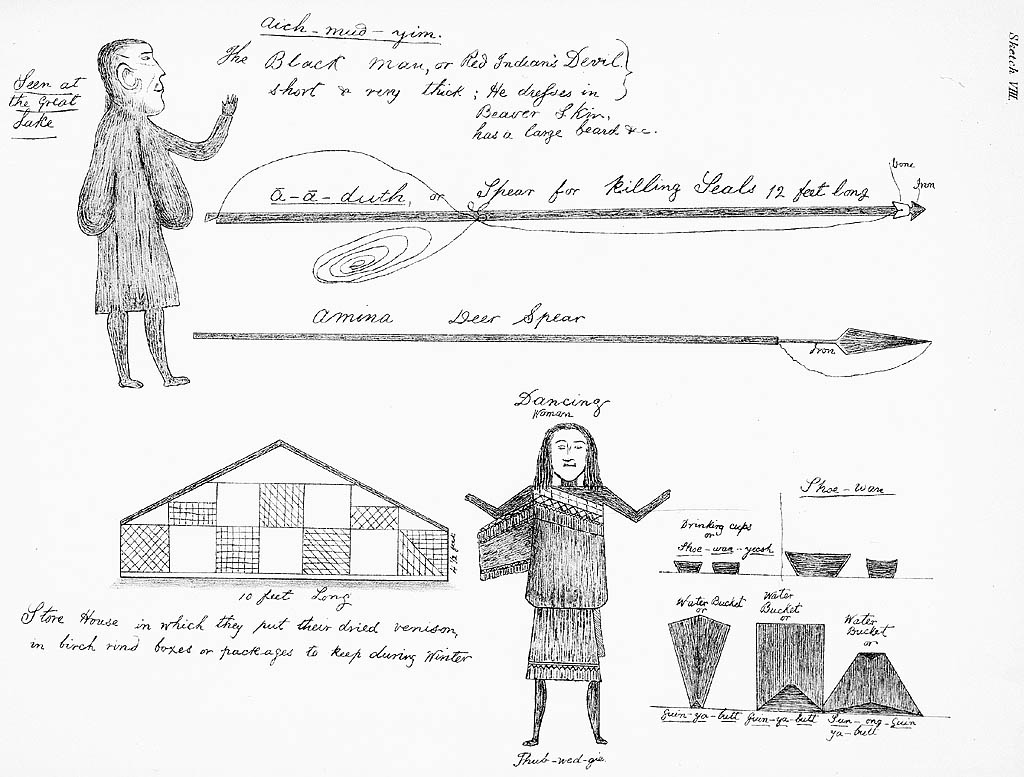

The Beothuk People were a hunter-gatherer nation who lived and hunted in extended family groups of 30-55 people on the island of Newfoundland. During the summer, they would gather at the coast and at the mouths of rivers to fish and socialise, and over the winter they would hunt caribou inland, living in balance with the ecosystem of the island.

It is believed that they were the first Indigenous People of the North American continent to have contact with Europeans. Historians believe that the Beothuk population was less than 1,000 people at the time of European contact in 1497, and by 1829, less than 350 years, the Beothuk people were extinct from Newfoundland.

To begin with the Beothuk people and European fishermen were able to share the island peacefully, with the Europeans returning to their homes each winter, and the Beothuk able to utilise the equipment including new metals, that had been left behind.

However, when word start to spread of the lucrative fishing opportunities in Newfoundland, Europeans began to establish permanent settlements in harbours and around the coast in areas used by the Beothuk people, cutting them off from their traditional fishing grounds and from the sea. As more Europeans arrived, they spread into the Beothuk’s new fishing grounds, forcing them inland completely and removing two of the three main food sources of the people, fish and seal. This in turn lead to over hunting of the caribou, which saw a decline in numbers that could not be recovered. The fur trade, of which the Beothuk were not a part, also had a huge impact on caribou numbers. This all changed the balance of the ecosystem on the island and led to the starvation of the Beothuk.

Violence between the peoples eventually ensued, however the European firearm was no match for the traditional bows and arrows of the Beothuk people, and many lost their lives, some where even hunted down by Europeans that viewed them as a threat.

The European introduction of tuberculosis, smallpox and measles further impacted the population. There are some arguments that question the severity of this impact, given nomadic and scattered nature of the population, however, there is no doubt that on a small population these new diseases would have had a profound effect.

A woman called Shanawdithit was believed to be the last survivor of the Beothuk people. She and her family, including her aunt Demesduit are the reason we know so much about their culture today, Demesduit being captured and Shanawdithit seeking help as she was starving. Shanawdithit died in 1829, her people being declared extinct. However, the Beothuk nomadic lifestyle meant that some bloodlines survived on the mainland, and their descendants are still keeping a people and their culture, thought to be long extinct, alive to this day.

Drawings by Shanawdithit (approx 1800-1829). National Archives of Canada Library.

The Spurriers

The Spurriers, who became one of Poole’s leading Newfoundland merchant families, appear to have come from the town of Wareham in the seventeenth century. Walter Spurrier, who was living in Fish Street in 1690, began as a sailor in the Newfoundland fishing fleets and later became a merchant in his own right. His sons followed him into the business, opening up the previously unexploited fishing grounds off St. Mary’s Bay, Newfoundland.

In 1747 one of the six Spurriers in the corporation was William, who was mayor of Poole on four occasions between 1784 and 1802. He took over the Poole firm of Waldren and Young and by 1785 had become head of one of the largest and most prosperous Newfoundland trading companies. The business success and wealth allowed William Spurrier to buy an estate, including Pergins Island, at Upton in the late 1700s. He had always dreamt of building a mansion.

Poole Quay courtesy of Poole Museum

After his wife Mary died in 1782, William re-married Ann Jolliffe, a young lady from another merchant family in Poole. Their son, Christopher Spurrier (1783-1876) inherited the Upton Estate from his father and married Amy Garland in 1814. Spurrier built Upton House between 1816 and 1818 ‘at great expense’ and presumably to impress his father-in-law George Garland, had the turnpike road diverted to enlarge the surrounding parklands. In 1825 he added the west wing.

Christopher was a spendthrift and gambler who let the business falter at the time that the Newfoundland trade was in decline at the end of the French Wars. He sought a seat in Parliament and did become MP for Bridport in 1820 (a position he held for less than 6 months after his opponent accused him of bribery), having mortgaged Upton House for £12,000 and having sold his Compton Abbas estate for £16,513 to finance the campaign.

His marriage was under strain and he neglected both family life and business. In 1825 he was forced to put the house and estate up for auction, having squandered his inheritance on gambling and a failed policitical career. Upton was eventually sold in 1828 to Sir Edward Doughty, formerly Tichborne. Paintings and plate were sold to pay off Spurrier’s mounting gambling debts and it is said that he wagered and lost his last silver teapot on a maggot race!

In July 1830 the firm of Spurrier, Jolliffe and Spurrier, which had failed to adapt to the general decline of the Newfoundland trade, collapsed owing £26,077. The company’s Poole and Newfoundland properties were sold, including a fleet of 11 ships and business premises in Placentia Bay, Oderin, Barren Island and the Isle of Allan. After the creditors had been paid, Amy Spurrier (d. 28 July 1841), who had lived largely apart from her husband after the crash, managed to recover £5,000 from his estate. Christopher Spurrier lived for some years in the Longfleet area of Poole but died penniless in 1876.